Medieval Lhc

My name is Gilles de Rouxville, a 14th-century Benedictine monk from the glorious Abbey of Cluny, and, like many of the Monks of Cluny, an expert in illuminated manuscripts.

My life could have flowed peacefully, in the serene silence of our blessed and beloved Scriptorium, but instead...

I was, God forgive me, very good at my job. I must confess that I saw it more as a path, a passion, a journey toward my personal idea of sanctity. Nothing could stop me; nothing was so rich, refined, precise, to the point of obsession, for my art.

Often, completely immersed in the elaboration of an illumination, I lost track of time. I felt neither hunger nor sleep nor cold, and in winter in Cluny there was a lot of cold, real cold, cruel, damp, biting, that stuck like a cursed tick, sucked your brain, froze your bones, and above all, your hands, your fingers, my sacred instruments!

But… but I, by now I was far away, I had truly fallen into one of my "earthly paradises," a sweet, lush eternal spring, with God, flowers, birds, unicorns.

I felt no pain, I was in ecstasy, totally lost and happy. I had real "visions" of the drawings, I had nothing else to do but illuminate, nothing to research, it was a gift.

I was, I thought, the "hand of God."

And this, however, greatly annoyed many of my brothers; they were monks, not saints!

The devil used me—I was his innocent conduit—to undermine my companions, instilling in them toxic envy, poisonous thoughts, even eternal hatred, if our Holy Rule had permitted it.

Every moment, every pretext, every opportunity was a good one to laugh at me, and even though it was strictly forbidden by our Holy Rule, I was often the victim of nasty pranks. Sometimes they didn't wake me for the night vigils, the first Divine Office at two in the morning, even though it was forbidden by Saint Benedict. They left me in my "paradises," forcing me to skip my frugal lunch, even though it was expressly forbidden and punished by our Holy Rule. In short, I was always, in one way or another, the object of ridicule and various forms of cruelty, even though I often didn't even realize it.

But that was the ugly side of the coin.

Then there was also the beautiful side, the light, the glory. God have mercy on me and my sinful pride!

Even the Abbot was proud of me; my small, precious masterpieces brought honor and prestige to our beloved Abbey, the "beacon of Christianity," as it was called then. They spread through the immense network of dependent abbeys and minor priories, even reaching isolated monasteries in the countryside or the most remote woods. I was even imitated, and badly, robbed of my art, and I was angry, God forgive me!

But, above all, my fame had reached even Avignon, the seat and earthly kingdom of our blessed Pope Innocent IV, who, even as Pope, was in great torment in his marvelous white palace.

Innocent, by name and by nature, he hardly slept anymore. Wrapped in his fine sheets of pure silk, he had lost his appetite and barely touched the crumbs of the delicacies reserved for him; not even a drop of his blessed and beloved Châteaux Neuf could pass down his sacred throat.

Pope Innocent IV was a devil for hair! The demons of doubt tormented him day and night. But why? What had really happened in the tranquil village of Saint-Genis-Pouilly?

Innocent didn't even know the name of this place, even before the "Miracle," but for some time, swarms of demons had been buzzing around this tiny village, a buzzing that was annoying to the Holy Ears and also very confusing.

More than buzzing, they were voices, fragments of stories, shards of legends. There were now rumors of the "Miracle of Saint-Genis," but it was only a convenient way of speaking.

Innocent could not afford to be mistaken, by his very nature as Pope.

He, Innocent, certainly had a dense network of informants; the Pope's eyes and ears were spread throughout the Christian West. They could take on very strange forms: ears half-eaten by leprosy, the hallucinated eyes of "God's fools," or, more sinfully, the languid eyes of magnificent courtesans.

But all the mouths, more or less whole, more or less slurred, more or less lustful, uttered the same kind of stories. Quite specific stories, for once, of a strange "ring-shaped hill" several leagues in diameter. On this "strange hill," hermits, witches, heretics, and a peripheral branch of the tards venus had immediately settled, like parasites. They had shared the ring-shaped forest. But, above all, there were the chasms; beneath that "strange hill," a world of darkness opened up.

And here, things smelled rather sulfurous. Innocent was supposed to bring Christian Light to these cursed places. But he also had to be discreet, a shadow, a breath, a silence. And, precisely in the silence, the light had appeared: Cluny! Yes, Cluny, his abbey, where he, Innocent IV, was blessed. For the Benedictine monks of Cluny, his monks, silence was a rule, written by their holy founder.

These monks were perfect for his quest, silent, but also great travelers, always wandering throughout the Christian world, from one abbey, daughter of Cluny, to another.

He, Innocent, had never had anything to do with such a "miracle," but there had been precedents and therefore also a modus operandi.

And Innocent also had a name in mind: the already famous Gilles de Rouxville, a monk of the glorious Abbey of Cluny, whose illuminated drawings Innocent already owned, which were his favorites among his precious collections.

Innocent IV had absolute faith in Gilles's art; whatever emerged from the "Miracle of Saint Genis," Gilles de Rouxville would illuminate it for the glory of God. And for his own.

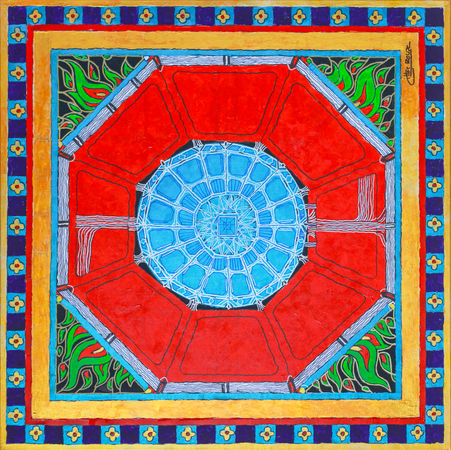

The images you find on the following pages are the transposition of Gilles de Rouxville's visions.